In 1974, when I was six, The Who released Quadrophenia. Too young to understand it, I felt it. The album starts with ocean sounds and on one track, Roger Daltrey sings, "I want to drown... in cold water!" It was my first encounter with suicide and I was drawn to it. I didn't know why, but I, too, wanted to drown in cold water.

As a kid in the mid-70s, living in Toronto's Regent Park Community Housing Project, I had no context for this desire. The only water of any depth that I'd been in was the community swimming pool, which I didn't enjoy because my uncle Paul thought throwing me into the deep end would teach me to swim. It didn't. I can still recall the face and red swimsuit of the lifeguard who dragged me to safety. This first drowning was formative: I never fully trusted a man again, and it caused me to mentally distance myself from my family for the first time.

A year later, my mother took my sisters and me to Kew Beach in eastern Toronto. We'd mess around on the sand, and I could go in the water up to my belly button. They were three and five years older, and the middle one could swim unsupervised. My eldest sister was disabled due to a stroke at six months; like me, she could walk in the water up to her waist.

These days, I visit Lake Ontario with my dog almost every day. Toronto beaches are awful when it comes to shoreline care. Driftwood, tree roots, grass, and stones — all where they shouldn't be. I don't remember the mid-seventies shoreline, but one visit, a log bobbed within reach. I straddled it and paddled with my arms. There must have been waves because I started to wobble and tip. I flattened myself to the trunk and embraced it. I quickly found myself on the underside, clutching the bark. Remember, it was summer, 1975. I'd seen Jaws. Everyone had seen Jaws. There was no way I was letting go of that log.

I came to on shore, lying on my back coughing water. My mother was at my feet, my ankles in her hands, and my sisters standing next to her, crying. If I was forced to say what had happened, I would guess that my mother pumped my legs until my stomach gave up the lake water. I'd seen the technique on The Flintstones. Whatever really happened, I've blocked it out. Drowning number two. Water and I weren't getting along.

At 27, I took my first flight. Toronto to Hawaii to Melbourne — 22.5 hours each way, with a month of winter sunshine in between. At Bell's Beach, I discovered the exhilaration of being churned by waves — it was like being ambushed by joy! If the woman I flew to meet hadn't been waiting on the hood of her vintage VW bug, I might not have walked out of that water. We drove 100 km to Bell's because I knew the location from Point Break, and I told her that I didn't know why, but "I just have to see it." Sixteen thousand kilometers for a wonderful woman I knew instantly I wouldn't uproot my life for. I liked her plenty, but I fell in love with the ocean.

My most recent drowning was in January, 2020. Inexplicably, I went into the South Pacific on a stand-up paddle board, also known as a SUP, in water shoes and street clothes. At the time, my uniform was dress shorts and a nice linen shirt. I spent almost four years traveling the world wearing that outfit exclusively.

I'd been living in Vanuatu on Efate Island for months, hired as a caretaker for Coco the dog and two anonymous chickens I called Thing One and Thing Two. The SUP was parked on the beach in front of my cabin, and I'd never touched it. Dragging it down the sand and paddling past the coral before learning to balance on my knees before paddling some more seemed too much the chore. Besides, who wants to be above the water when they can be in it?

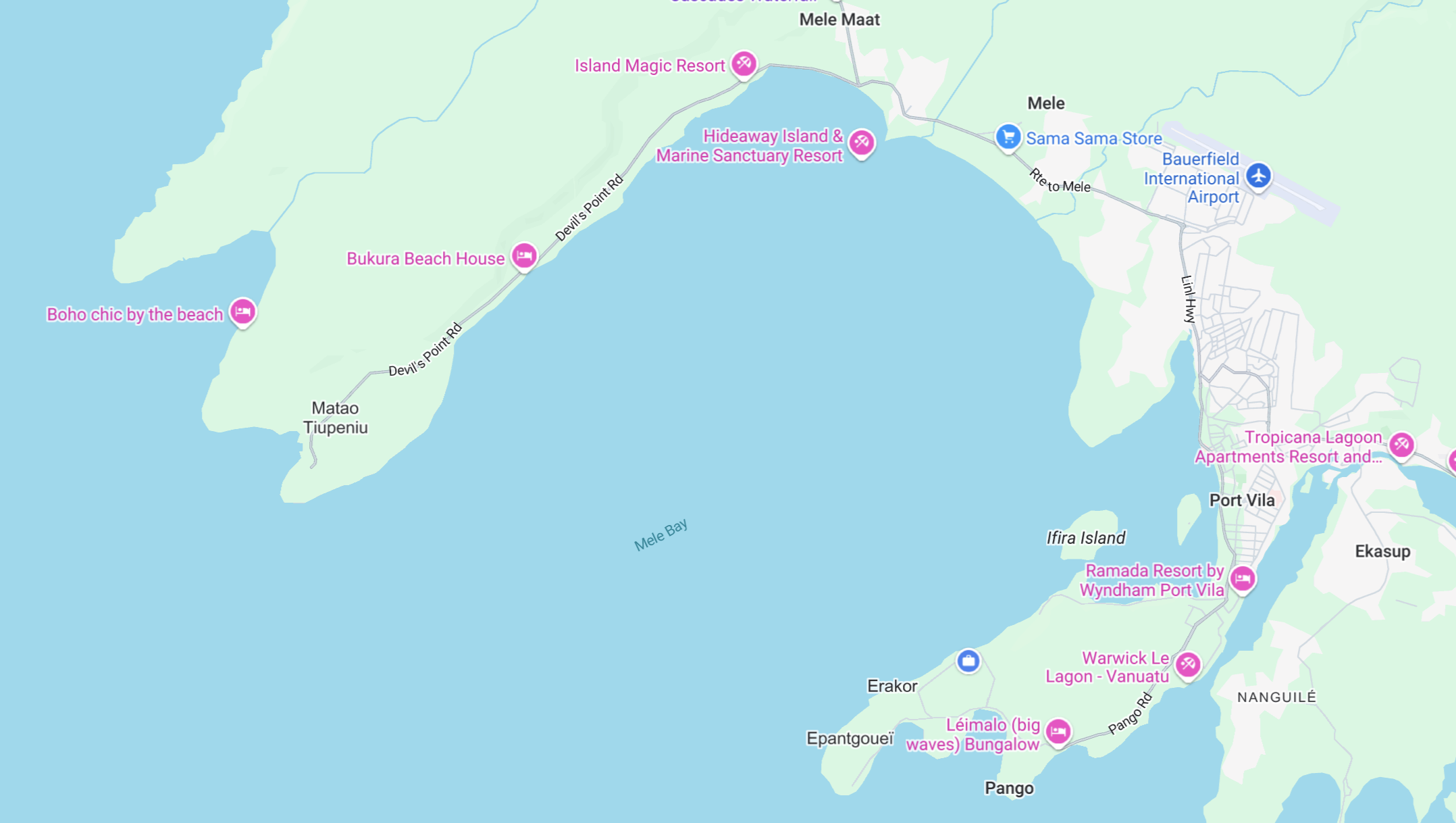

But there I was, standing atop Mele Bay, known locally as Paradise Cove. When I turned around to see how far I'd come, I saw that I'd gone considerably farther than expected. I'd covered probably two and a bit kilometers — far! — the cove being about eight and a half wide, shore to shore. It was a gorgeous day, as are most on the island.

Chuffed, I started to paddle back.

After ten minutes with no progress, I felt like I was now going backwards, towards the far side of the bay. The paddle seemed useless until I lowered myself to my belly and started paddling with my arms like a surfer trying to mount a cresting wave. That was useless. My options were to give up and hope I ended up on the opposite side of the bay; continue paddling; or swim. I chose option three. First, I fastened the paddle to the top of the board via the foot straps, then dove into the water. The SUP was leashed to my ankle and, since it wasn't mine and its value was higher than my nomad-lifestyle could afford, I'd be dragging it home. You're rolling your eyes, but my reasoning was sound, even as my understanding of physics wasn't.

I'd flown to the other side of the planet to get away from the hounding failures of my "real life," only to waste more of it in this heavenly country. When a line from a movie entered my head, I laughed at the absurdity: "I just wanted to leave my apartment, maybe meet a nice girl, and now I gotta die for it?!"

I hadn't checked the tide schedule and was caught in its turning. Exhausted, I climbed onto the board and lay on my back. The water wasn't calm, but I could float. I should have paid more attention. I am weak and inexperienced. I sat up and looked to the opposite side. It was closer, but I wasn't drifting to it. I was being dragged out of the cove to the sea, proper, which made me clear-eyed and decisive. I undid the leash and dove back into the water, heading toward my shore, though directly towards a neighboring property rather than the further distance to my own.

I was making middling progress when I felt a hand on my bicep. In one motion, someone pulled me from the water and turned me around, my feet and hands settling on a ladder as if I'd done it many times before. At the top, I faced a group of pie-eyed tourists. The man who grabbed me said they'd found the SUP, which caused them to search for its owner. "The kid spotted you."

The kid, who looked about 12, was beside his mother and there were half a dozen other adults, all out for a scuba diving lesson I'd definitely ruined. He looked fascinated, confused, and annoyed at the drenched, exhausted man in street clothes. Someone in the crew asked where I was headed and I pointed towards Lakatoro. He called to the driver — "Sal's!" — and the boat swung around and immediately that's where we were going.

"So..." said the kid. "What was the plan?" I realized they might think I was trying to kill myself. Who heads out on the water in street clothes?! "Just..." I said, but didn't finish. The whole thing was so ridiculous. When I'd been taking in water, my overriding thought wasn't, Oh my god, I'm going to drown or What were you thinking? It wasn't even Help! It was, What now?! This probably tells you something about my state of mind.

My rescuer said, "We can't take you to shore due to the coral, but we'll get you close." I nodded and picked up the SUP. The woman next to me pointed to the Angelfish Villas, saying she'd be there a few more days if I wanted company. I caught a Melbourne accent and remembered Biccan, the Aussie I'd lived with for a month in 1995, who'd watched Bell's Beach have its way with me while perched on the hood of her yellow Beetle. I wasn't sure if this woman was offering a lifeline or chatting me up, so I invited her to drop by Lakatoro. As I spoke, I knew she wouldn't. I imagine she still tells scuba stories not of colorful clownfish and coral, but of a rescued well-dressed Canadian who later stood her up.

We got as close to the shore as possible without damaging the coral. I turned and said, "Thanks for saving my life," hopped off the boat onto the SUP, and headed home.

Coco was on shore barking at the boat and then at me as I struggled to drag the board back to its home on the sand. I turned to wave goodbye to the boat, but it was already a distance away.

I took a quick shower and put on dry clothes. Though it was mid-afternoon, I poured myself a drink and sat on the patio. Suddenly, a black heron landed a few feet from me. I wondered if I was hallucinating, as I didn't think they were in this part of the world. Did she have a message for me? Or had she flown in to chastise and call me a fool? You are complicit in the conditions you're trying to escape. I reached for my camera, but Coco came barking and the bird took off. The egret gone, I heard a "Hello" and saw an elderly ni-Van walking towards me from the main gate. He asked after Sal and John, and I told him they were in Australia until March. He introduced himself as Brightly and said he'd been down the beach at Geoff and Lorraine's.

He asked, "Did you see the crazy guy on the paddle board?" I nodded. "Is he a guest here? It looked like the boat dropped him off right out front." I told him the man was staying at Paradise Cove, two properties down the beach.

"Lucky you. People with death wishes make terrible customers."

"But great lovers," I said.

He ignored my quip and tossed his chin up. "Were you swimming?"

"I just showered." Though true, he didn't believe me.

"If you see the paddle board man, tell him Brightly says he's reckless."

I told him I'd pass it on.

I saw him eying my whiskey, so I asked if he wanted a drink. He nodded and sat down while I went to fetch a glass and ice. When I returned, he was standing again. He gestured down the beach towards Geoff and Lorraine's. "We were all having a good laugh until we weren't," he said. "Understand?"

I did. He tapped the table with both hands and turned to go. His back to me, I heard him mumble, "Life's more delicate than we think."

"Lukum yu," I said in bislama.

"Lukum yu," he answered.

I poured his ice into my drink and sat down. I put my coaster on top of my glass and picked up my camera. I waited for the black heron to return with her message, but she never did.