In November, I received copies of two books by writer and walker Craig Mod. I've been a fan of his for many years, but these are the first of his books I've purchased. Shipping from Japan to Canada, on top of the cost of the books, was what had always stopped me in the past, but I do my best to support artists directly when I can so decided now was the time.

Kissy by Kissa and Things Become Other Things, hand-wrapped in specialty paper

If you're not familiar with Mod, he's mostly known for his work in the book world. He also has a wonderful podcast on bookmaking called On Margins, though he might have killed that as it's been a long time since he's put out an episode. It's well worth listening to if you're into creating things.

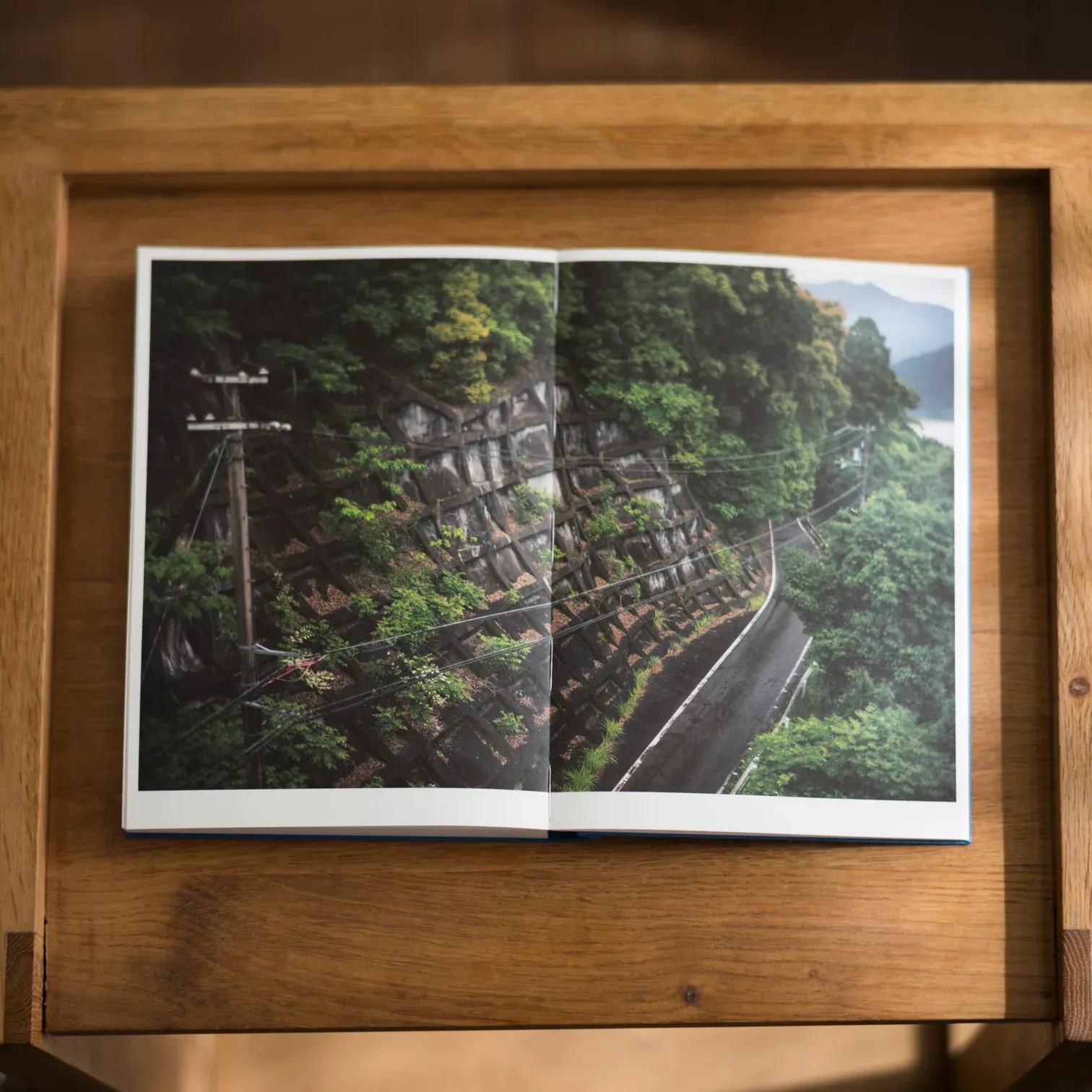

Since Craig is a walker and a writer, these books are about walking.

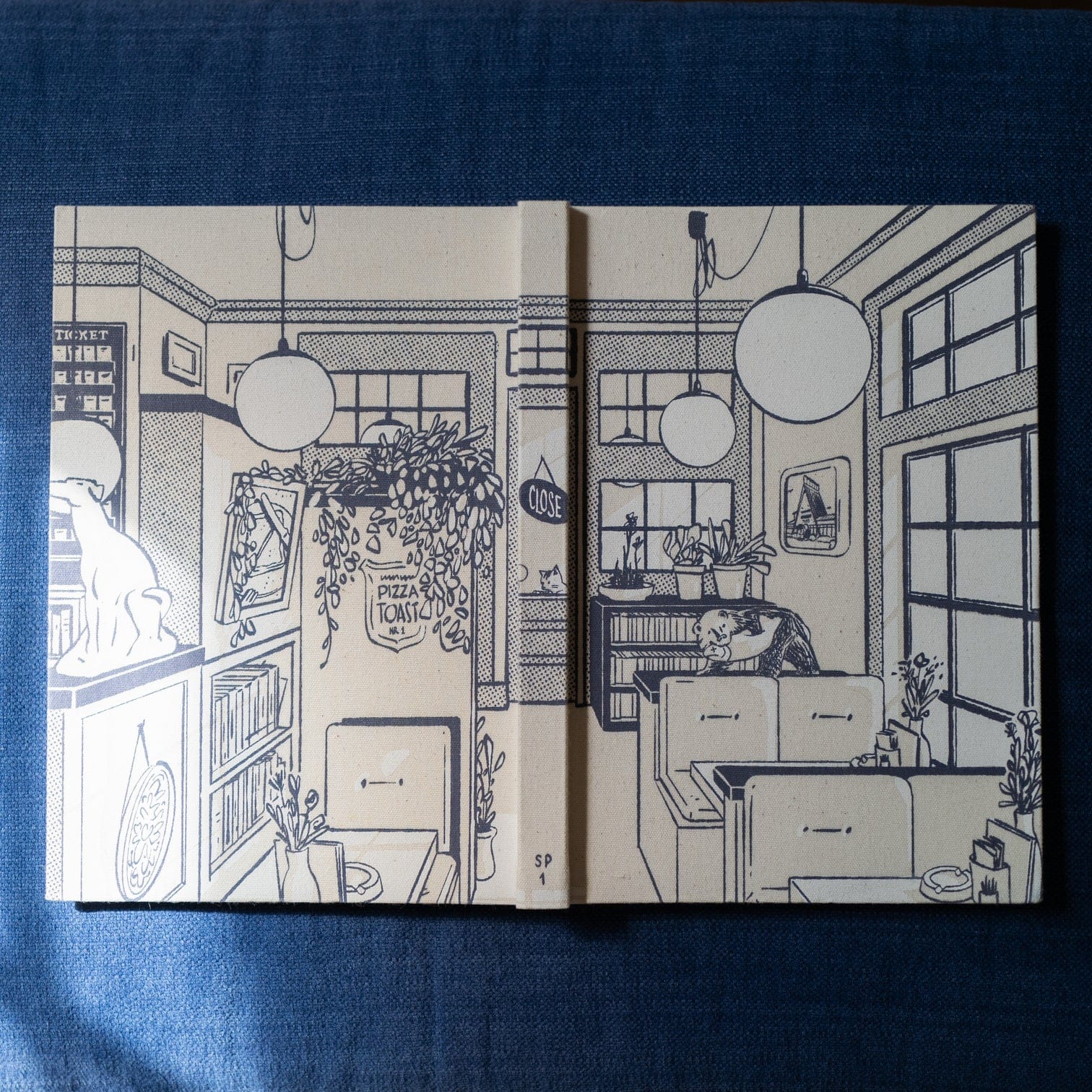

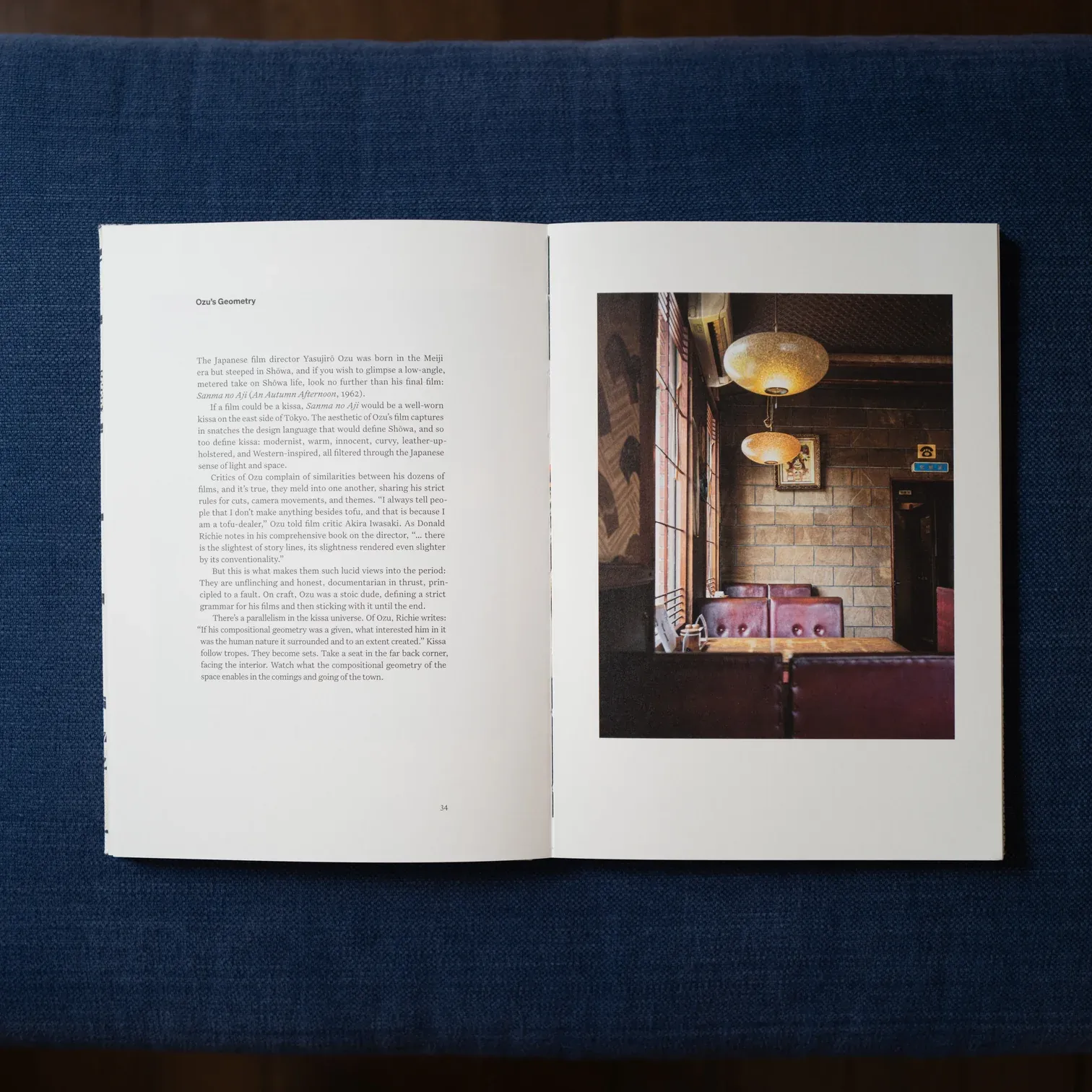

Craig describes Kissa by Kissa as "a book about walking 1,000+km of the countryside of Japan along the ancient Nakasendō highway, the culture of pizza toast (pizza toast!), and mid-twentieth century Japanese cafés called kissaten."

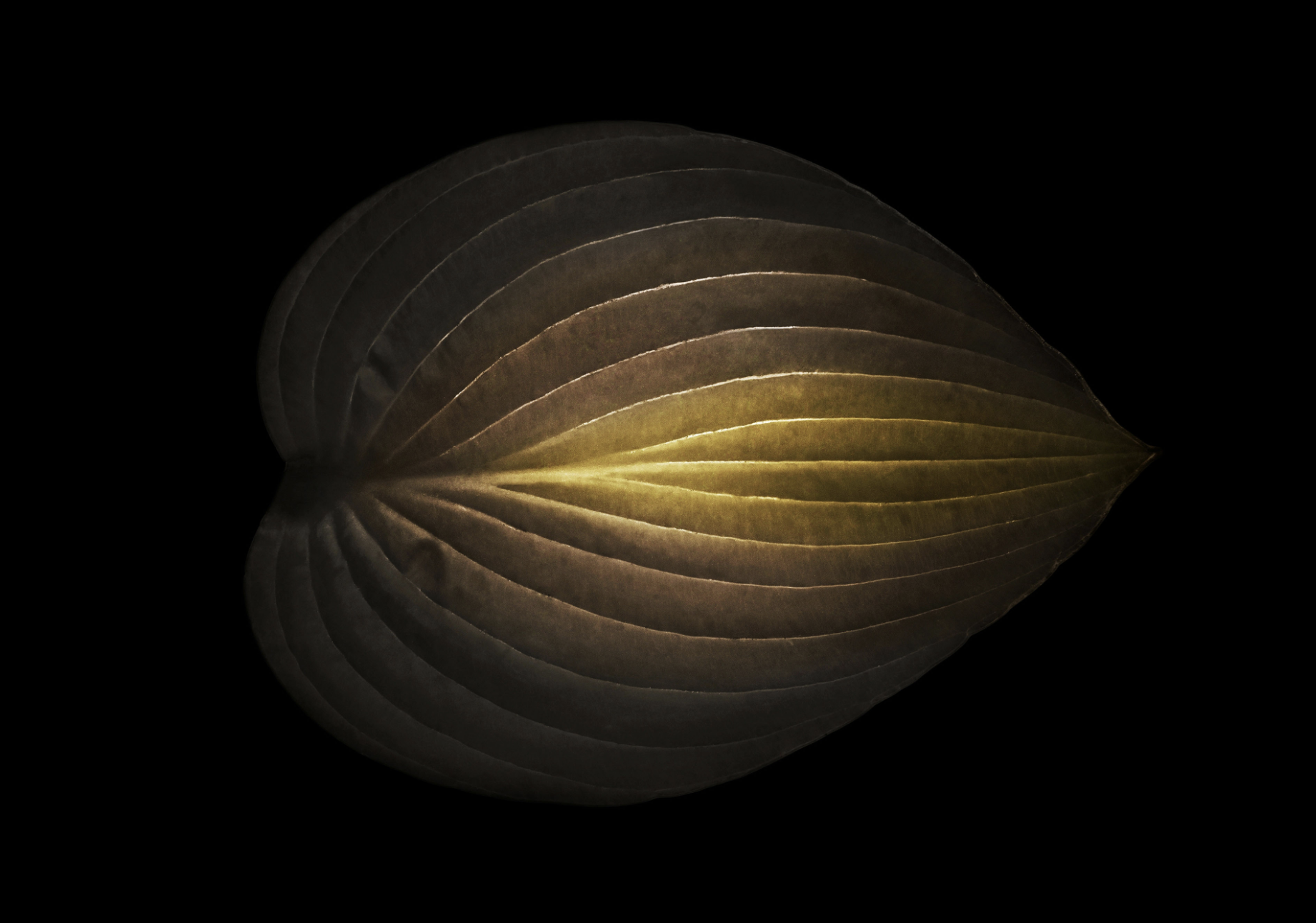

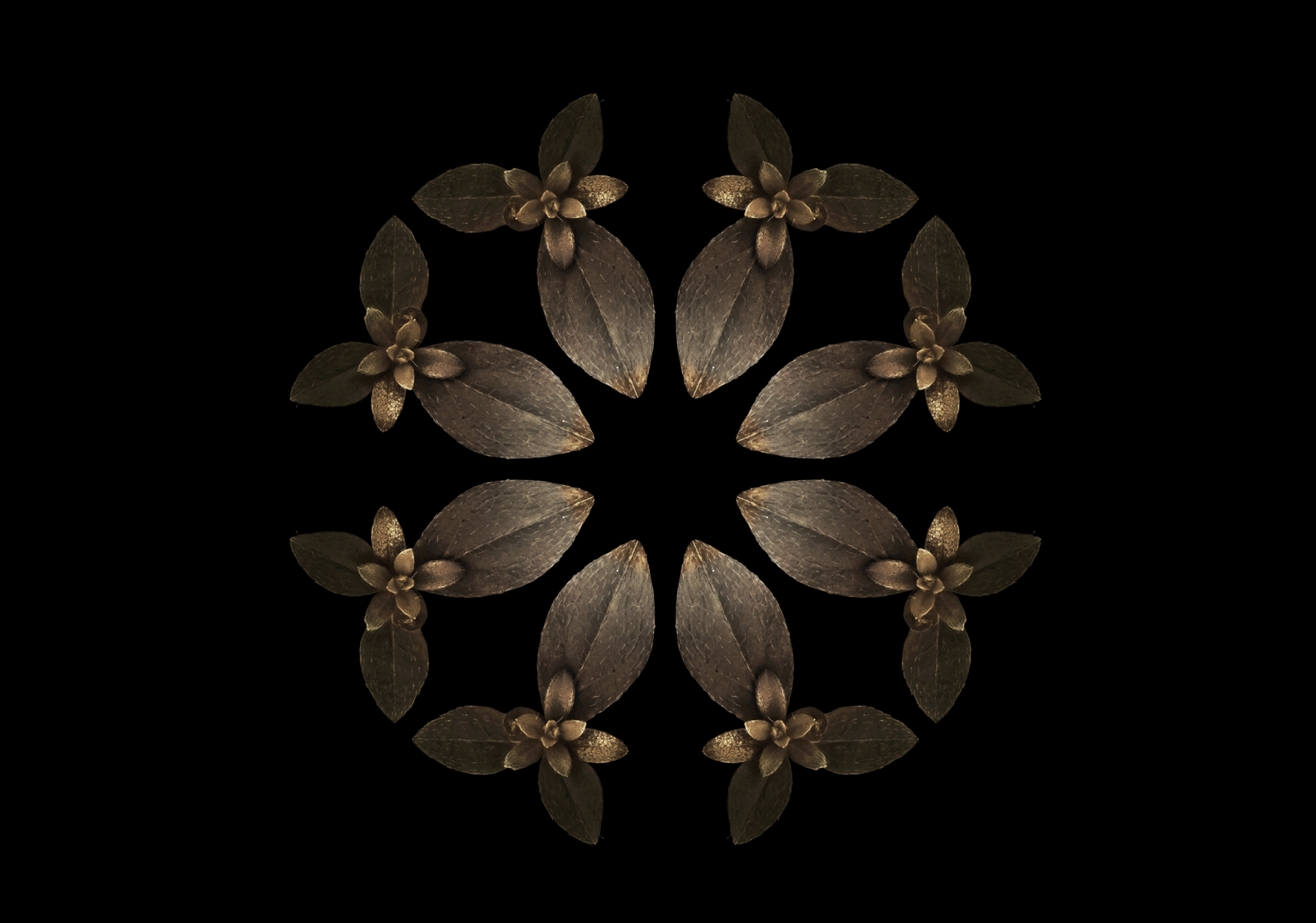

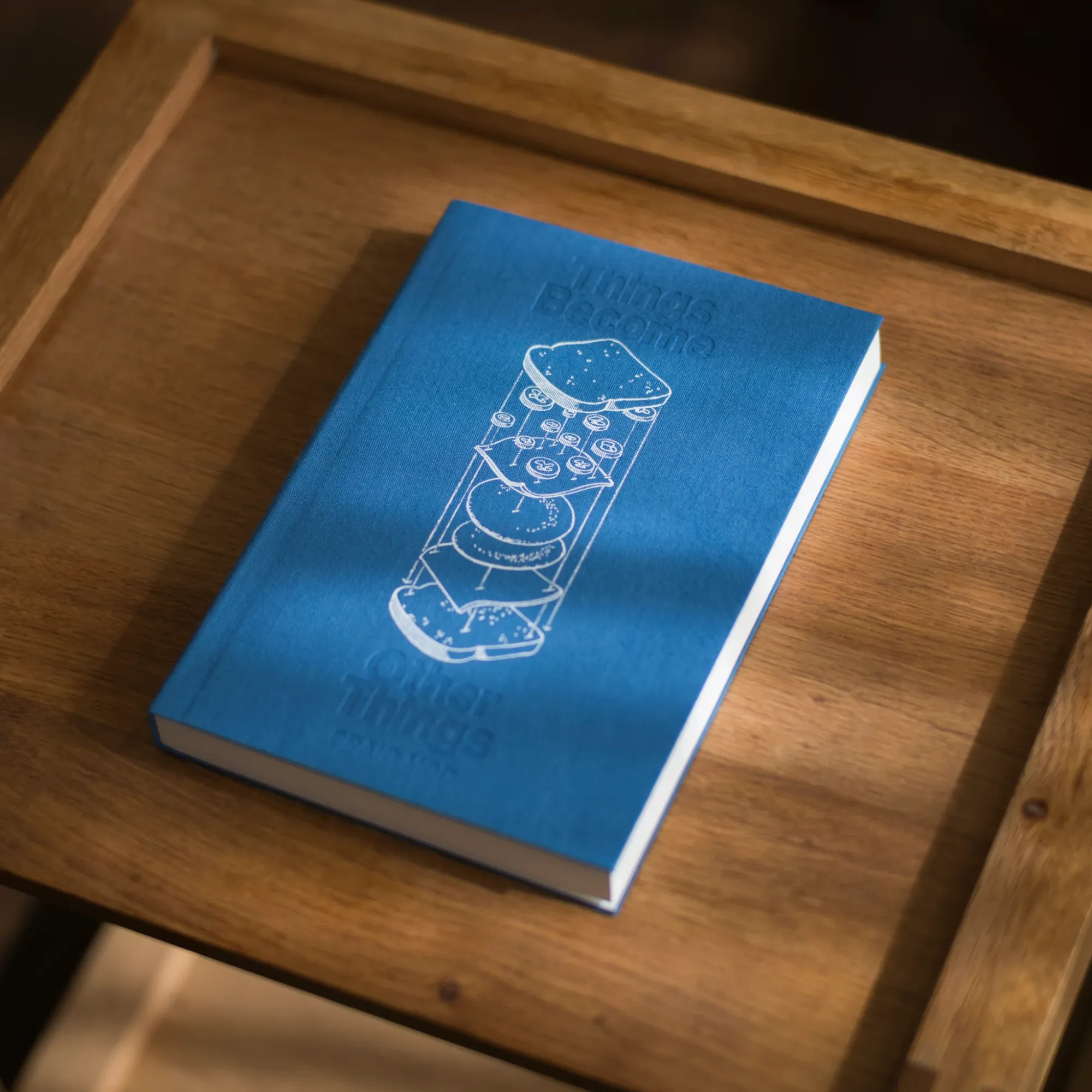

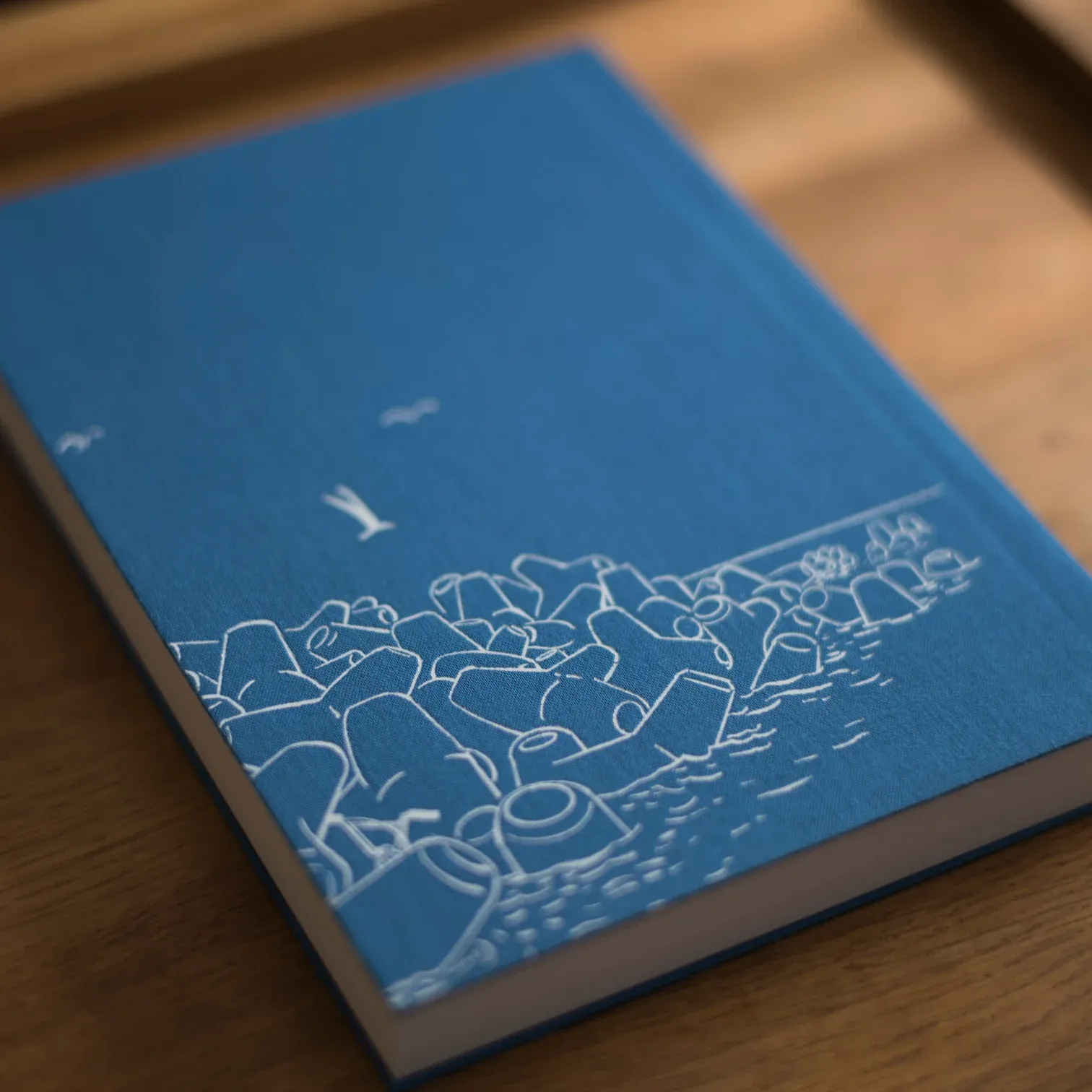

Craig's books are gorgeous. Cloth-bound with debossed covers. The paper is lovely to touch and the photos and essays are wonderful:

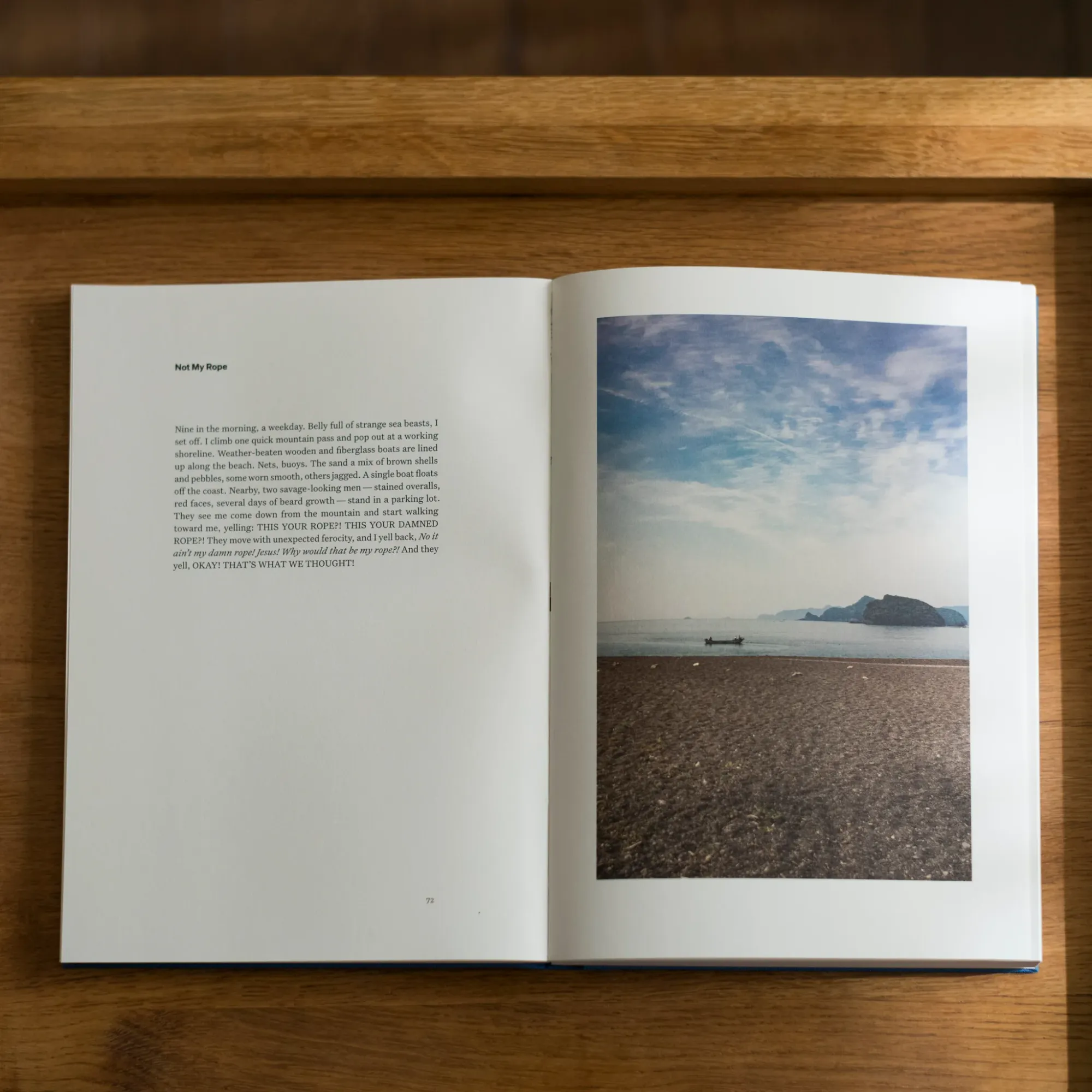

Things Become Other Things is Craig's latest book. He describes it as "a 30 day walk in Japan. A memoir. Fishermen, foul-mouthed kids, and terrible miserable wonderful coffee."

Things Become Other Things by Craig Mod

You can purchase the fifth edition of Kissa by Kissa here. The first edition of TBOT is here. Both titles are cheaper for members of Craig's Special Projects. Those memberships are how Craig makes his living.

If you'd like a better overview of Craig's work, you can find it here.

Anecdote Alert

These books are the kinds of things I used to bring in for customers of my shop, Volver — beautiful items that I personally own and can recommend — before I stopped carrying non-records. This was an effort to spread awareness and get better prices for my customers by eliminating the cost of shipping.

I did this most successfully, book-wise, with Wendy Erskine's Dance Move, a brilliant collection of short stories which still hasn't been published in Canada. I can't recall how many copies I brought in (20 or so), but they all sold out and still no other shop in the city took it upon themselves to import copies.

I have no idea if Craig would be into this (offering me bulk, wholesale pricing), but I'd consider approaching him if enough Bell Ringers wanted me to try.