Kumi Oguro has taken photos of segmented bodies for more than 20 years. I find them oddly compelling.

Daisy // Passage // Turn // Thread (clockwise)

Many more on Oguru's site.

Kumi Oguro has taken photos of segmented bodies for more than 20 years. I find them oddly compelling.

Daisy // Passage // Turn // Thread (clockwise)

Many more on Oguru's site.

Every day, thousands of Cease and Desist letters are issued, telling people to stop what they’re doing. What a bummer! That’s why we created: The Continue and Persist Letter. A official-lookinglegalletter that encourages and uplifts people, one that tells people to keep doing what they’re doing! Surprise someone you appreciate by sending them a Continue and Persist Letter.

More at Continue & Persist.

While in the South Pacific, I tried Kava, a legal drink made from the Kava plant and which has mild effects on the nervous system.

Instantly, upon drinking it, my lips began to tingle and then feel numb and a warm calm came over me. The taste is dreadful, sort of like muddy water, and it doesn't help that you drink from a dirty coconut shell that is shared by others.

You get Kava at Kava Bars, which usually open when the sun goes down. They advertise themselves with a single, dim roadside colored lightbulb, usually green or red. Here's a Kava bar in daylight in Vanuatu:

A woman I befriended on the island Efate had a husband who died of liver failure due to his addiction to Kava.

I was reminded of the drink today after reading about Betel Nuts, which I'd never heard of before: This addictive nut is driving record rates of cancer – yet millions continue to chew it. Fascinating.

Here's Drew Binksy on it:

Millions of people are turning to AI for companionship. They are finding the experience surprisingly meaningful, unexpectedly heartbreaking, and profoundly confusing, leaving them to wonder, ‘Is this real? And does that matter?’

ROVR describes itself as Radio Reinvented:

It's live right now, or you can comb through the Archive.

There's also an app for iPhone or Android.

What I've heard so far has been top-notch.

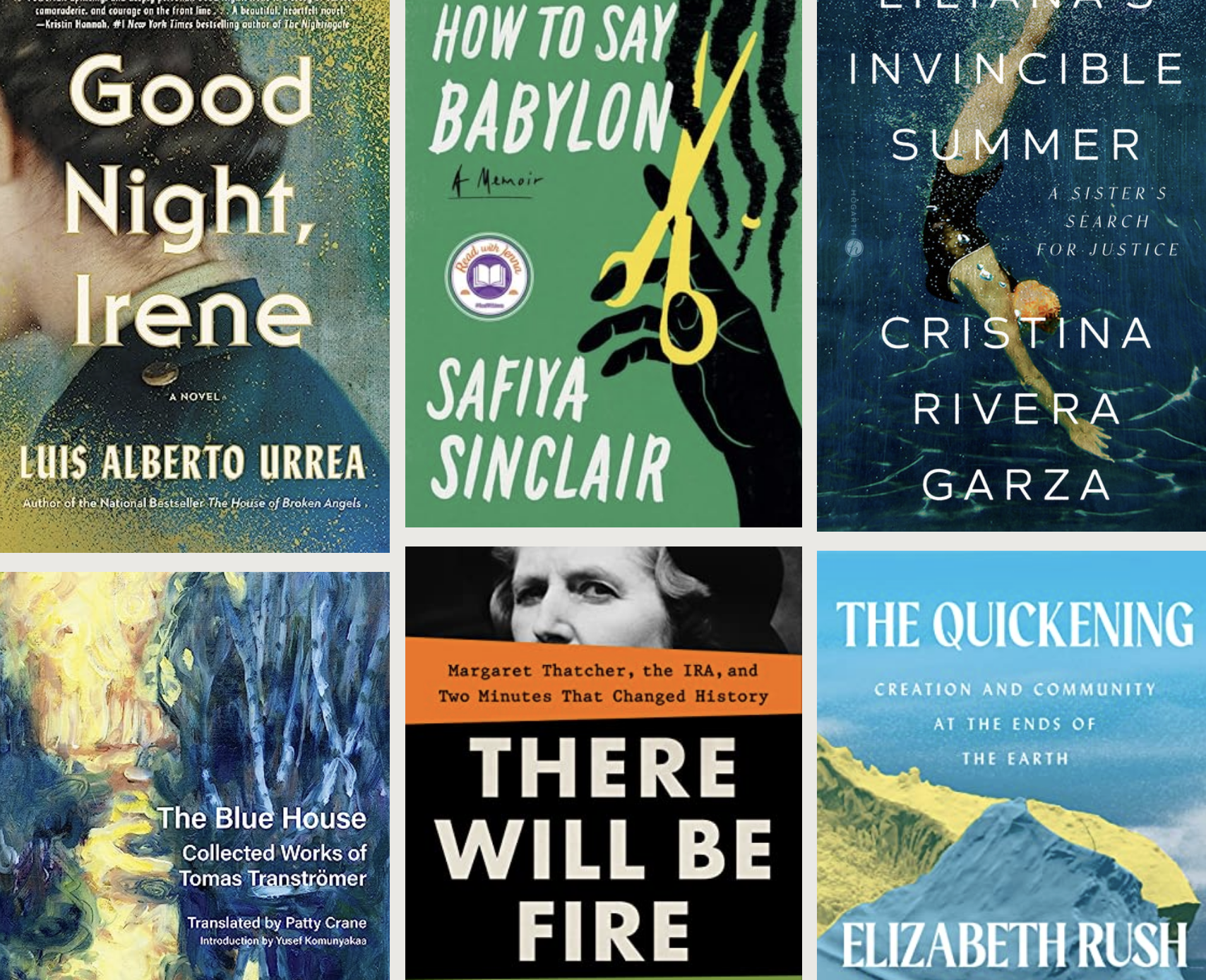

NPR's Books We Love offers up 12 years and counting of their favorite books. Some great filters as well. For example:

Terrific resource, very well presented.

I previously posted about 12 Pentagons Hand-made footballs. They've just dropped a new one, limited to 1000 pieces: 32 Bit Mesh.

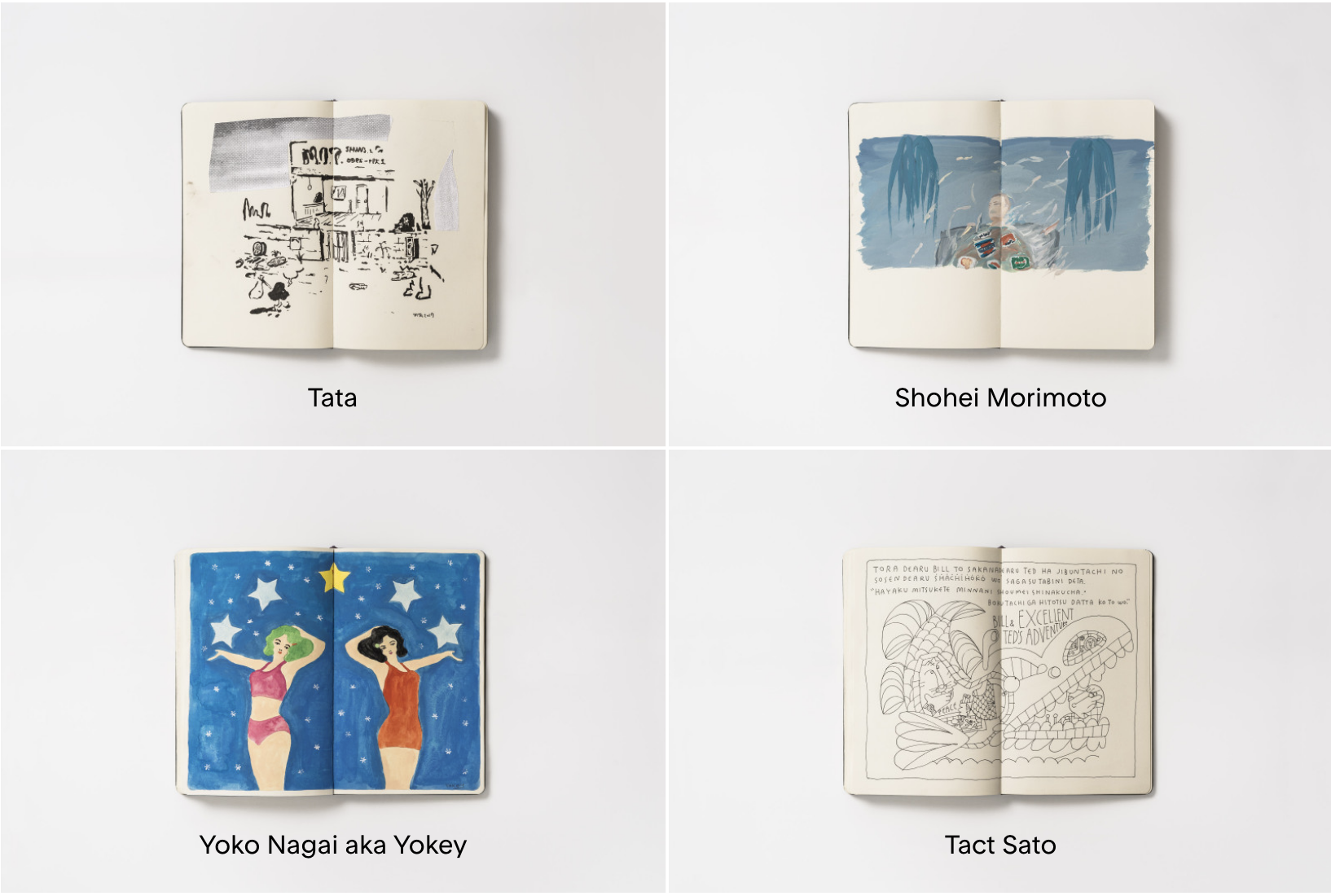

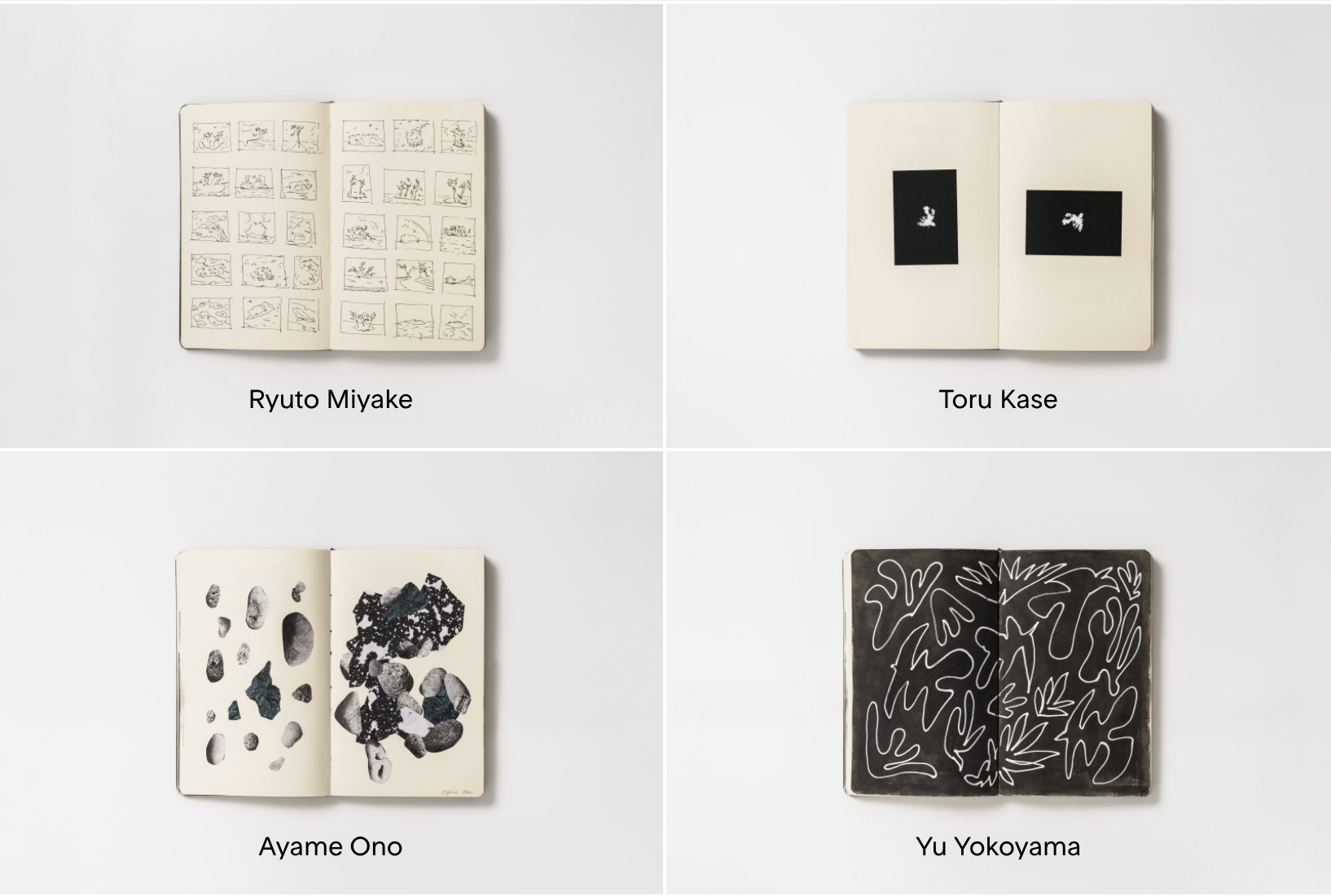

Two Pages is a series of nomadic sketchbooks shared by designers, artists, and illustrators around the world.

Since 2012, Two Pages connects local and international creative communities through raw creativity and spontaneous mark-making. It is an ongoing effort to record, spread and exchange ideas through the hand-to-hand journey of each book.

Past cities include Barcelona, Tokyo, Antwerp, Mexico City, Tehran, Cape Town, London, and many more. Toronto is happening right now.

You can read an interview with creators on It's Nice That and view Sketchbooks from all cities on Two Pages.

My record store no longer carries new vinyl (used only), but I thought my customers may want to know that Mississippi Records is releasing Yo La Tengo's soundtrack to Kelly Reichardt's 2006 film Old Joy on vinyl for the first time in February. You can pre-order here. You can sample the first track below.

James Lake is known for his phenomenal cardboard sculptures, some of them self-portraits.

His latest piece is stop-motion animated short called Another Day. Lovely work:

More on Lake's site.